Neuroangiostrongyliasis (Rat Lungworm)

Report a Case

Disease Reporting Line:

(808) 586-4586

What to Know

- Clinicians in Hawaiʻi should have a high index of suspicion for neuroangiostrongyliasis as rat lungworm disease is endemic in all of the islands in the State of Hawaiʻi. Early diagnosis and treatment are important to reduce the long-term sequelae associated with this disease.

- *NEW Updated (07/15/2025) testing guidance for clinicians is available here. A more sensitive RT-PCR assay to diagnose neuroangiostrongyliasis is now available at the Hawaii SLD. The assay can be performed on CSF; there is no minimum CSF eosinophil threshold requirement to order this test.

- Suspect cases should be reported to the Department of Health (DOH) Disease Reporting Line to facilitate prompt and accurate diagnosis.

- Rat lungworm disease can be prevented by eliminating snails, slugs, and rats founds near houses and gardens, avoiding eating raw or undercooked snails or slugs, and thoroughly inspecting and rinsing produce using potable water.

- The incubation period can range from a few days to more than 6 weeks, with the median time from exposure to symptoms being 1-3 weeks.

- Individuals with symptoms should consult their healthcare provider for more information.

About This Disease

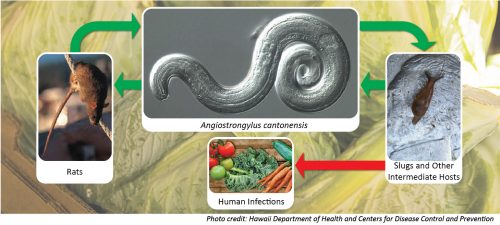

Neuroangiostrongyliasis, also known as rat lungworm, is a disease that affects the brain and spinal cord. It is caused by a parasitic nematode (roundworm parasite) called Angiostrongylus cantonensis. The adult form of A. cantonensis is only found in rodents. However, infected rodents can pass larvae of the worm in their feces. Snails, slugs, and certain other animals (including freshwater shrimp or prawns, land crabs, and frogs) can become infected by ingesting these larvae; these are considered intermediate hosts. Humans can become infected with A. cantonensis if they eat (intentionally or otherwise) a raw or undercooked infected intermediate host, thereby ingesting the parasite. For more information on the life cycle of A. cantonensis, visit the CDC website. The CDC has a video that provides information about what rat lungworm disease is, where it is found, how its transmitted, and how to prevent its spread.

Figure 1. Life cycle of Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the parasite which causes neuroangiostrongyliasis (rat lungworm disease).

Figure 2. Juvenile Parmarion martensi on a nickel (Credit: DOH)

Figure 3. Veronicella cubensis (Credit: Rob Cowie, UH Manoa)

Figure 4. Achatina fulica (Credit: Jaynee Kim, Bishop Museum)

Why is this a public health concern in Hawaiʻi ?

While some infected people do not have any symptoms or experience mild symptoms for a short period of time, sometimes A. cantonensis infection can cause a rare type of meningitis (eosinophilic meningitis). A. cantonensis is the leading cause of infectious eosinophilic meningitis in Hawaiʻi and other regions in the world. Further, rat lungworm disease is preventable. It is important to report cases to DOH so that we can monitor the number of cases and promote disease prevention activities in our community. Suspect cases should be reported to the DOH Disease Reporting Line to facilitate prompt, accurate diagnosis, and appropriate patient management. Rat lungworm disease is of concern for both residents and visitors to Hawaiʻi.

Risk in Hawaiʻi

Rat lungworm disease is endemic in the State of Hawaiʻi. Human cases and infected intermediate hosts (snails and slugs) have been identified on all of the islands. Since the risk for infection is present statewide, the recommendations for preventing infection should be followed regardless of where in the state you reside or if you are a visitor. Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for neuroangiostrongyliasis, as symptoms can be non-specific and evolve to more specific symptoms over the following weeks.

The case counts in Table 1 show laboratory-confirmed cases of rat lungworm disease identified in the state for 2024 and 2025. The actual burden of disease is likely higher because diagnosing the disease can be difficult.

Table 1. Number of confirmed cases of neuroangiostrongyliasis (rat lungworm disease) identified in Hawaiʻi for 2025 and 2026, as of March 2, 2026

| Year | Hawaii County | Honolulu County | Maui County | Kauai County | State Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026 | 2 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0) |

| 2025 | 4 (0)* | 0 | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 6 (0)* |

*One case was reclassified from 2024 to 2025 after review of data.

The number of confirmed cases of angiostrongyliasis in previous years is reported here.

Signs and Symptoms

The clinical presentation can vary and present differently with each individual. Symptoms usually last between 2–8 weeks; however, symptoms in confirmed cases of rat lungworm disease have been reported to last for longer periods of time.

Infection may cause a spectrum of disease ranging from mild, self-limited headache to severe, neurologic debilitation, coma, and/or rarely death. Because of the varied clinical presentation, cases may go without medical treatment and unreported. Additionally, other conditions can present similarly to rat lungworm disease. Individuals with symptoms should consult their healthcare provider for more information. Early diagnosis and treatment are important.

Table 2. Summary of rat lungworm disease (neuroangiostrongyliasis) clinical symptoms by adults and children.

| Age Group | Earlier Symptoms* Within hours to a few days of ingestion | Symptom Progression* Ranging from few days to a few weeks |

|---|---|---|

| Adults | • Nausea with/without vomiting • Abdominal pain • Diarrhea • Lethargy (tiredness) and insomnia (inability to sleep) • Fever • Cough • Pruritus (itching) with/without rash • Hypersensitivity to touch including burning pain with itchiness | • Severe and constant headache • Muscle pain, neck stiffness • Paresthesia and hyperesthesia, frequently described as itching, pain, tingling, crawling or burning sensations • Diplopia (double vision) • Photophobia (light sensitivity) • Limb weakness • Bowel or bladder dysfunction • Seizures |

| Children | • Rash • Fever • Irritability • Drowsiness/lethargy • Poor appetite • Nonspecific abdominal pain • Muscle twitching • Convulsions or seizures • Increased sensitivity to touch Age-specific symptoms In children <3 years: • Weakness of the extremities (arms and legs) In children 3-18 years: • Vomiting • Headache | • Aversion to touch or being held • Developmental regression in sitting, crawling, walking, talking (in children <3 years) |

Transmission

You can get neuroangiostrongyliasis by eating food contaminated by the parasitic larvae. In Hawaiʻi, these larvae can be found in raw or undercooked snails or slugs. Sometimes people can become infected by eating raw produce that contains a small, infected snail or slug, or part of one. Since the rat lungworm parasite larvae cannot survive desiccation (removal of moisture), slime left by infected snails and slugs will not be able to cause infection after it dries. Neuroangiostrongyliasis is not spread person-to-person.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing neuroangiostrongyliasis can be difficult, as there are no readily available blood tests. Lumbar puncture (LP) is an essential part of the evaluation of suspected neuroangiostrongyliasis.

- In Hawaiʻi, neuroangiostrongyliasis diagnosis can be confirmed with a real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test, performed by the DOH State Laboratories Division (SLD). Providers can call DOH disease reporting line to request SLD testing. The RT-PCR test detects A. cantonensis DNA in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

- Eosinophilic meningitis is the hallmark of neuroangiostrongyliasis. CSF eosinophil counts may be absent or low early in the course of the disease, therefore repeating LP and the CSF RT-PCR lab test is recommended if neuroangiostrongyliasis is still suspected.

- There is no CLIA-approved diagnostic test available to detect prior infections of neuroangiostrongyliasis.

- A presumptive diagnosis is based on:

- exposure history (e.g., history of travel to areas where the parasite is known to be found or history of ingestion of raw or undercooked snails, slugs, or other animals known to carry the parasite),

- clinical signs and symptoms suggesting neuroangiostrongyliasis, and

- laboratory finding of eosinophils in CSF (via LP).

Treatment

Early diagnosis and treatment are important. It is not necessary to wait for laboratory results before initiating treatment. Treatment of angiostrongyliasis may include high dose corticosteroids, serial lumbar punctures for symptomatic relief of headaches, and anthelminthic therapy with agents such as albendazole. Published clinical guidelines can help guide medical management. Given that lumbar puncture may not be performed in all suspected cases and that establishing a definitive diagnosis can be challenging, healthcare providers should not delay clinical decision-making while awaiting laboratory test results. Empiric treatment may be warranted in cases with strong clinical suspicion of neuroangiostrongyliasis.

For additional information on treatment, refer to:

Prevention

To prevent neuroangiostrongyliasis:

- Do not eat raw or undercooked snails, slugs, freshwater shrimp/prawns, land crabs, and frogs

- Do not handle snails or slugs with bare hands: use gloves, or any other material/tool to keep a barrier between your skin and the snail/slime

- Only drink potable water; do not drink from garden hoses

- Washing produce, to dislodge and remove any snails or snail slime, is recommended to prevent possible infection

- Thoroughly inspect and rinse produce using potable water

- Do not soak leaves of leafy greens; it is recommended to rinse each leaf under running potable water

- Rat lungworm larvae cannot withstand extreme temperatures, so cooking or freezing produce will also prevent infection

- Boil snails, freshwater prawns, crabs, and frogs for at least 3–5 minutes

- Freeze vegetables for at least 24 hours

- Eliminating snails, slugs, and rats founds near houses and gardens might also help reduce risk exposure to cantonensis, which can be achieved through pesticide baits, traps, rodent-proofing your home, and sanitation

- Maintain your water catchment system and replace filters regularly

- Cover and protect your catchment tank, as slugs can crawl up the tank and get into the water

- Always cover drink containers when you’re outside to stop slugs and snails from crawling inside

See slug jug recipe to help you reduce the number of slugs on your property:

Additional Resources

Airport Baggage Claim Monitors

Airport Baggage Claim Monitors

Big Island Invasive Species Committee (BIISC)

Big Island Invasive Species Committee (BIISC)

- Rat Lungworm Disease

- Community Slug and Snail Reports – Report a slug or snail sighting & see community reports

University of Hawai’i at Manoa, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources (CTAHR)

University of Hawai’i at Manoa, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources (CTAHR)

University of Hawaii Daniel K. Inouye College of Pharmacy

University of Hawaii Daniel K. Inouye College of Pharmacy

Clinician Resources

Rat Lungworm Decision Aid for Clinicians in Hawaiʻi

Rat Lungworm Decision Aid for Clinicians in Hawaiʻi

Rat Lungworm Disease: What Clinicians Need to Know

Rat Lungworm Disease: What Clinicians Need to Know

2021 Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of neuroangiostrongyliasis: updated recommendations

2021 Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of neuroangiostrongyliasis: updated recommendations

CDC – Angiostrongyliasis Resources for Health Professionals

CDC – Angiostrongyliasis Resources for Health Professionals

State Laboratories Division Specimen Submission Form (81.3)

State Laboratories Division Specimen Submission Form (81.3)

Scientific References From 2020-2025

For scientific references prior to 2020, refer to the bibliography in “Archived Information.”

- Ansdell, V., Kramer, K., McMillan, J, et al. (2021). Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of neuroangiostrongyliasis: updated recommendations. Parasitology, 148(2), 227-233.

- Baláž V, Rivory P, Hayward D, Jaensch S, Malik R, Lee R, Modrý D, Šlapeta J. 2023. Angie-LAMP for diagnosis of human eosinophilic meningitis using dog as proxy: a LAMP assay for Angiostrongylus cantonensis DNA in cerebrospinal fluid. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 17: e0011038.

- Chance MD, Noel AD, Thompson AB, Marrero N, Bula-Rudas F, Horvat CM, Green J, Armstrong JE, Levent F, Dudas RA, Shaffren S, Samide A, Martinez K, Stockdale K, Chancey RJ. 2024. Angiostrongylus cantonensis meningoencephalitis in three pediatric patients in Florida, USA. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 13: 639–642.

- Cowie, RH., Ansdell, V., Panosian Dunavan, C., Rollins, RL. (2022). Neuroangiostrongyliasis: Global spread of an emerging tropical disease. Am. J Trop. Med Hyg. 107(6): 1166-1172.

- Howe, K., Bernal, L., Brewer, F. et al. (2021). A Hawaii public education programme for rat lungworm disease prevention. Parasitology, 148 (2): 206-211.

- Jacob, J., Steel, A., Lin, Z., et al. (2022). Clinical efficacy and safety of Albendazole and other Benzimidazole Anthelmintics for Rat Lungworm disease (Neuroangiostrongyliasis): A systematic analysis of clinical reports and animal studies. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 74(7), 1293-1302.

- Jacob, J., Steel, A., Howe, K., Jarvi, S. (2023). Management of Rat Lungworm Disease (Neuroangiostrongyliasis) using Anthelmintics: Recent updates and recommendations. Pathogens, 12(1): 1-6.

- Jarvi, S., Prociv, P. (2020). Angiostrongylus cantonensis and neuroangiostrongyliasis (rat lungworm disease): 2020. Parasitology, 148(2): 129-132.

- Odani, J., Sox, E., Coleman, W., Jha, R. & Malik, R. 2021. First documented cases of canine neuroangiostrongyliasis due to Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Hawaii. Journal of the American Animal Hospitals Association 57: 42-46.

- Paredes-Esquivel, C., Foronda, P., Panosian Dunavan, C. & Cowie, R.H. 2023. Neuroangiostrongyliasis: rat lungworm invades Europe. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 108(4): 857-858.

- Rollins RL, Medeiros MCI & Cowie RH. 2023. Stressed snails release Angiostrongylus cantonensis (rat lungworm) larvae in their slime. One Health 17: 100658.

- Sears WJ, Qvarnstrom Y, Dahlstrom E, Snook K, Kaluna L, Baláž V, Feckova B, Šlapeta J, Modry D, Jarvi S, Nutman TB. 2021. AcanR3990 qPCR: a novel, highly sensitive, bioinformatically-informed assay to detect Angiostrongylus cantonensis infections. Clin Infect Dis. 73: e1594–600.

- Yates, J., Devere, T., Sakurai-Burton, S., Santi, B., McAllister, C. & Frank, K. 2022. Case report: Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection presenting as small fiber neuropathy. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 107(2): 367-369.

- Zunt, J., Barczak, M., Chang, D. 2025. Case 5-2025: A 30-Year-Old Woman with Headache and Dysesthesia. The New England Journal of Medicine, 392 (7): 699-709.

Archived Information

2018 Legislative Report on Rat Lungworm Disease Initiatives (PDF)

2018 Legislative Report on Rat Lungworm Disease Initiatives (PDF)

Hawaii State Department of Health Rat Lungworm Fact Sheet (PDF)

Hawaii State Department of Health Rat Lungworm Fact Sheet (PDF)

Angiostrongyliasis (Rat Lungworm) Info Sheet (PDF)

Angiostrongyliasis (Rat Lungworm) Info Sheet (PDF)

Bibliography of Scientific Articles Published prior to 2020 (PDF)

Bibliography of Scientific Articles Published prior to 2020 (PDF)

Last reviewed August 2025